How do you recognize poetry?

Marvin Bell asks the question in his poem, “The 3 Corners of Reality,” and he answers his own question in the next line.

--It looks like poetry.

And that’s as good an answer as any, better than most. What’s the one thing that differentiates poetry from any other written form? It’s written in lines. And yes, I know you can split hairs and blur definitions and find exceptions, but we’re not concerned about them right now.

A poem is something that looks like a poem. If you look at a series of printed pages from across the room, as if they were eye charts, you can tell which ones are the poems from their shape on the page. If it’s blocks of text that stretch all the way from one margin to the other, it’s prose. If it’s irregular margins with a lot of white space to the right, it’s a poem. Well, either a poem or a grocery list. And if you come in closer, you can quickly tell the poem from the grocery list, because each line of the grocery list only has one logical purpose—the naming of something to be bought. A poem, generally speaking, is going to have two different logics working in counterpoint – the logic of grammar and the logic of the line. Sometimes they’ll coincide, sometimes not.

So the way a poem looks on the page is important.

We live in an age when the sound of poetry is made much of, and rightly so. Poetry was originally an oral art form. Today, rap and slam poetry have gone a long way toward shifting the focus back to poetry as a performance art, but they aren’t the only ones. That other stuff, the stuff they call academic poetry or literary poetry or whatever, has found its oral footing as well. Whereas at one time, unless it was Dylan Thomas doing the reading, a poetry reading was likely to be a soporific event, so many of today’s poets are accomplished readers, and a poetry reading can be first rate entertainment. Poets take oral presentation of their work seriously, and take the time and practice to learn to do it well.

So an important part of poetry is presentation.

But that’s not only true of the oral tradition of poetry. Presentation on the printed page is also important. It’s one of the crucial ways in which poetry communicates to us.

A poem with short lines and lots of white space immediately sends a different signal to us than a poem with longer lines, even before we read the words. A poem broken up into four line stanzas carries certain expectations with it. If we see three of those stanzas, followed by a couplet, we think “sonnet,” either with pleasurable anticipation or dread. We see a poem that has eight lines together, a break, and then six lines together, and again, “sonnet!” We may find those expectations confounded, as in the sonnets of Halvard Johnson, but that’s part of the experience of art: expectations met, expectations confounded. A poem that presents itself on the page with highly irregular line lengths and stanza lengths tells us that we can expect to have any expectations confounded.

Marvin Bell, in his poem that lets us know that you can tell a poem because it looks like a poem, gives us all sorts of visual evidence that this is a poem. The lines are short. There are stanza breaks.

And when he gets to the “looks like poetry” part, he gives us another visual clue that the content of this stanza is going to be different from the rest of the poem: the left hand margin is indented. Further, every other line begins with a dash, so it looks even more indented. And the visual cues really do signal a shift in the strategy of the poem: the indented stanza is a series of questions and answers, with the dashes serving to set the answers on a different plane than the questions.

These visual cues, available to the reader of the poem on the printed page but not o the listener of a poem read aloud, are nothing new. John Donne’s “Song (Go and catch a falling star)” does it. The poem is written in stanzas of lines, iambic tetrameter except for the seventh and eighth lines, which are monometer. The rhyme scheme is quatrain (ABAB), couplet (CC), tercet (DDD). The quatrains look different from the couplets on the page in that the B lines are indented; there’s no indentation for the couplet. The couplets also sound different, in that they all have feminine endings, so although they’re still strict tetrameter they sound longer. And the monometer lines are deeply indented, making them stand out visually as well as aurally.

Why? Well, just because it’s kinda neat. In the language of movie and TV writing, there are “Easter eggs,” little self-referential images tucked into a scene, to “reward viewers who watch closely—and to celebrate their own craft,” according to one definition, and a pretty good one at that. Yeah, Marvin Bell and Jack Donne and the boys are celebrating their own craft, and we can celebrate along with them.

William Carlos Williams really celebrated his own craft with his triadic, or stepped line, about which a truly frightening amount of criticism has been written. Williams introduced this form in his epic Paterson, and he used it in a number of other poems, including “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower.” (https://poets.org/poem/asphodel-greeny-flower-excerpt)

I’ve said that a poem gives you visual cues on the page by its white spaces, including the spaces between stanzas. In the case of “Asphodel,” that’s true and it isn’t. The triadic line is written in tercets, with the left margin of each line staggered across the page. Instead of stanza breaks, each new tercet is indicated by the left margin returning all the way to the left. Or maybe it’s not that way at all. Williams preferred to think of each tercet as a single trimeter line, with each unit representing a metric foot, or if it didn’t, a variable foot. Or a unit of breath, which we’ve discussed before. Critic Eleanor Berry lists six different ways other critics have described Williams’ line: (1) a temporal unit, each step being equal in duration to any other; (2) a stress-based unit, each step containing a single major stress; (3) a syntactical unit, each step being a single phrase or clause; (4) a unit of meaning; (5) a unit of phrasing, the triadic lineation constituting a score for performance; (6) a visual unit.

Definition 5 suggests that the poem as an aural experience can match the visual experience, and Robert Pinsky, reading “Asphodel” on YouTube, follows that to a considerable extent, except where he doesn’t, and where he doesn’t pause is where one might most likely expect a pause. He pauses at the end of nearly every triadic step, but he doesn’t pause at the end of the line, instead swooping across each enjambment.

So the aural experience of a poem is different from the visual experience. But what if no aural experience is possible?

There is no way one could read aloud e. e. cummings’s poem about loneliness and a falling leaf, which is so evocative, the way it drifts down the page, but all that would be lost if you tried to read it aloud.

The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets often wrote poems that depended on the placement of words, or even single letters, on the page for their effect. Joan Retallack’s collection, Afterrimages, consisted of poems constructed in two parts. The first part was fragmentary phrases, perhaps found phrases, laid out in lines and possible to read aloud. The second part (and here’s a sample) was scattered letters, as though the poem had been written on a wall, partially erased, and then almost completely erased. Wallace Stevens talked about the beauty of innuendoes -- the possibility, on some level of the imagination, of recreating the blackbird's whistle from the silence afterwards. Retallack pushes it one step further—the only thing moving is the eye of the blackbird, and it’s not moving either.

And then there’s Aram Saroyan’s celebrated one word poem

Lighght

which Saroyan describes thus: “The difference between ‘lighght’ and another type of poem with more words is that it doesn’t have a reading process. Even a five-word poem has a beginning, middle, and end. A one-word poem doesn’t. You can see it all at once. It’s instant.”

This means that “lighght” doesn’t actually have a seeing process, either. It defies Marvin Bell’s (and my) definition of a poem as something that looks like a poem. One word, or one collection of letters, doesn’t look like much of anything on a page. It doesn’t give you that visual strategy that says “poem.” And yet, the way it looks on the page is everything.

Finally, one more kind of poem that needs to be seen to be fully appreciated: the concrete, or shaped poem. These are frequently dismissed as gimmicky, but they don’t have to be. They’re part of the visual presentation of poetry.

When we think of shaped poems, we are very likely to think first of George Herbert, the 17th Century poet whose devotional lyrics often took the shape of religions icons. “The Altar” is in the shape of an altar, “Easter Wings” in the shape of angels’ wings. Here, the shapes accentuate the passionate conviction of Herbert’s belief.

Lewis Carroll used a shape for “The Mouse’s Tale” in Alice in Wonderland. The cleverness of the form and the cleverness of some of the language (“Really, this morning I’ve nothing to do”) can lull you into thinking it’s a clever trifle, but it winds down, more and more grim, to the mouse’s death.

John Hollander’s “Swan and Shadow” is a tour de force of shape – a swan and its reflection – in the service of a poem about the ephemeral nature of beauty, poignantly and ironically presented in a form often called “concrete.”

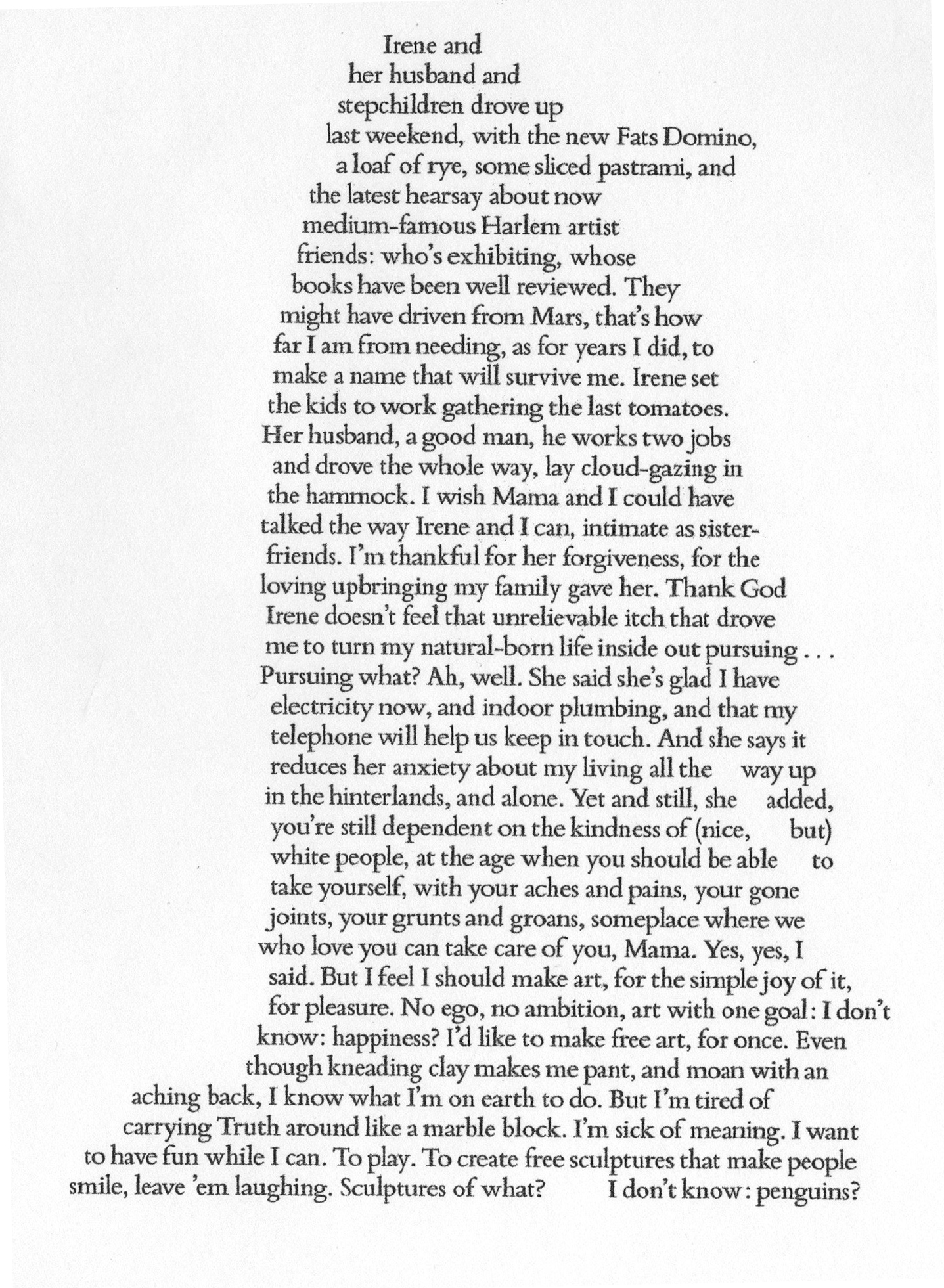

The most vivid, and most apropos recent use of shaped poetry is found in Marilyn Nelson’s Augusta Savage: The Shape of a Sculptor’s Life.

Augusta Savage was a sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance, and Nelson’s book is a biography in verse and a celebration of her life and work.

Biography and poetry are strange bedfellows. Biography is straightforward and inclusive—often very inclusive. A biographer may take over 1000 pages to give us the life of James Joyce or Ulysses S. Grant. Lyric poetry is episodic, fragmentary, impressionistic, synechdocal.

Nelson, in Augusta Savage, manages to capture both ends of this fantastic beast. Her book really is a biography of a remarkable African American woman and an important artist, a portrait of an age and the people who inhabited it (seen through Savage’s portraits of those people, like Marcus Garvey), and at the same time it’s a collection of poems, each of which stand alone, and each of which give us the insight and the gifts of language that we hope for in poetry.

And—what could be more appropriate in a collection of poems about a sculptor—some of the poems are sculptural works themselves: shaped poems that outline the shapes of the statues that were their inspirations. There are poems in the shape of the sculptor’s hands and a musician’s harp, of ducklings and rabbits, of Aleksandr Pushkin and Marcus Garvey. And this one, in the shape of a penguin.

What to stuff a penguin with? Why, in her old age, should a sculptor who has come sixty years since her first childhood attempts to make ducklings out of clay, who has fashioned busts of Pushkin and Garvey, of socially prominent authors like Poultney Bigelow (on commission), who has created 35 statues for the World’s Fair, decide to make a penguin? Savage’s penguin is simple and elegant, cute and formal.

Nelson’s penguin is what’s left when the temporal glow of fame has receded, when the loved ones in your life matter, but the creative ember that still glows inside matters even more.

And it looks like a penguin.